From pairs to graphs: evaluating protein–protein interaction models on network biology

Published:

Roughly a quarter of late-stage clinical failures are attributed to safety issues (UoT). And on the healthcare side, adverse drug reactions (ADRs) account for ~6.5% (≈1 in 16) of hospital admissions in the UK (BMC). It’s tempting to think one drug → one protein → one effect, but a lot of safety risk isn’t just about your target protein, it’s about the network your target lives in.

Imagine you’re designing a therapeutic to inhibit a protein implicated in disease. You find a clean-looking target, validate binding, and check that it isn’t annotated as “essential.” Six months later, in vivo results come back showing unexpected toxicity, effectively discontinuing the candidate.

What happened? A common answer is biology’s “second-order effects.” Your drug didn’t just perturb Protein X, it perturbed the interaction neighborhood around Protein X, destabilizing connected pathways and complexes. You tugged one thread and the sweater unraveled.

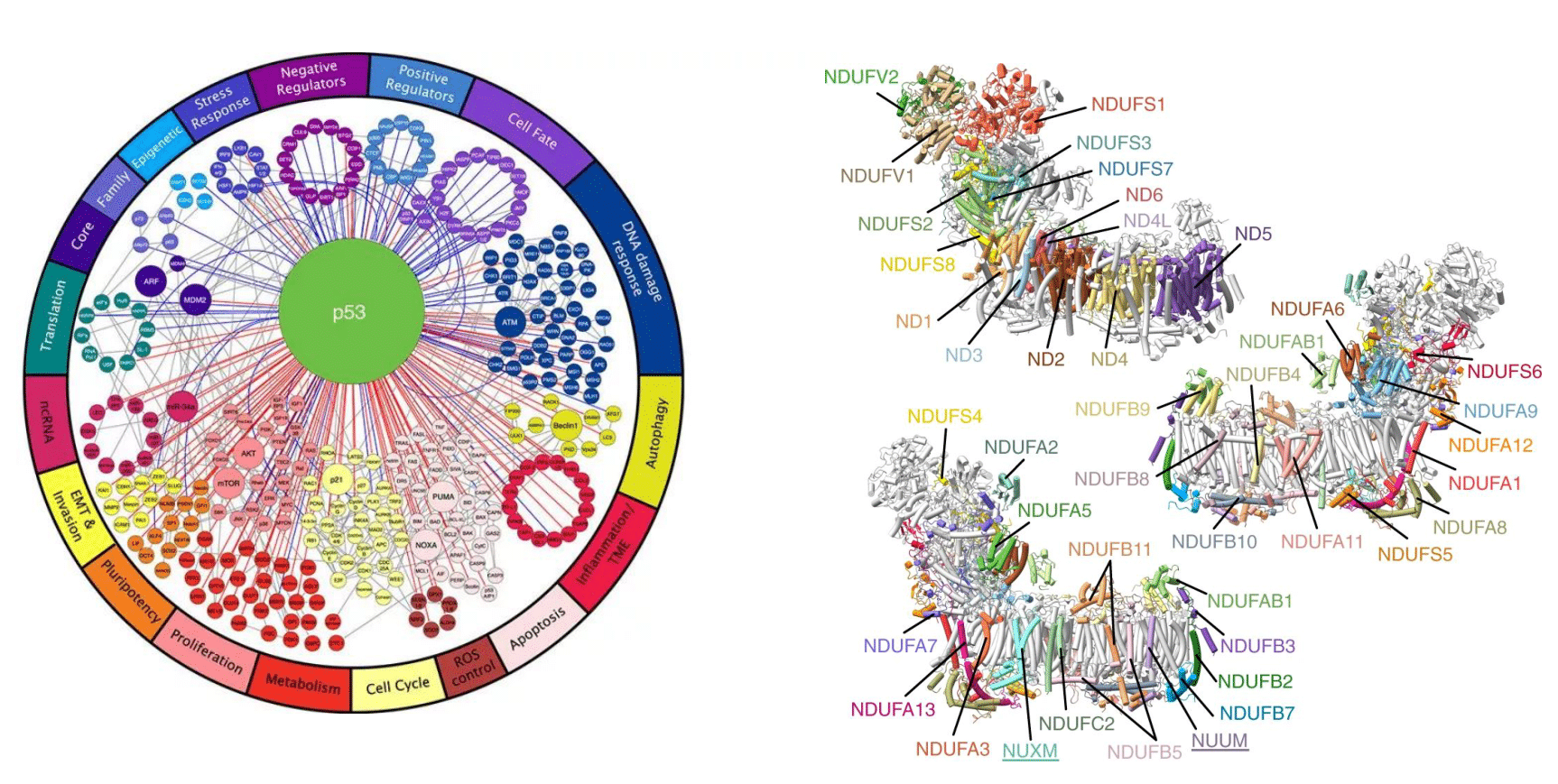

In cells, proteins don’t work in isolation: they form multi-protein machines and sit inside regulatory networks. For example, mitochondrial complex I consists of ~45 distinct proteins. Another example is transcription factor (TF) wiring: a single TF like p53 regulates several hundred genes, coordinating key cellular programs. So when you perturb one protein, you’re rarely affecting a single edge (“does A bind B?”). You’re affecting a graph: hubs, modules, complexes, and the flow of information through them.

The network of p53 interactions (left, MSKCC) and mitochondrial complex I (right, Nature).

The network of p53 interactions (left, MSKCC) and mitochondrial complex I (right, Nature).

The current gap: we mostly grade PPI models on pairs

Recent years have seen strong progress in predicting protein–protein interactions (PPIs): homology/sequence-similarity tools, structure-based approaches (e.g., Boltz-2, AlphaFold3, OpenFold3), and protein language models (pLMs) that can be fine-tuned for interaction prediction.

But evaluation often defaults to a simple question: given (A, B), is the label 0 or 1? That’s useful, but it can mislead. A model can score well on pairwise metrics while producing a network that’s biologically “wrong” in ways that matter: too dense, missing key hubs, fragmenting true complexes, or breaking modular structure. Pairwise AUC won’t tell you that.

A more useful question is:

“If I perturb Protein X, what happens to its interaction neighborhood?”

That pushes us toward reconstructing an interaction network, not just scoring pairs.

Enter PRING: network-level evaluation for PPI prediction

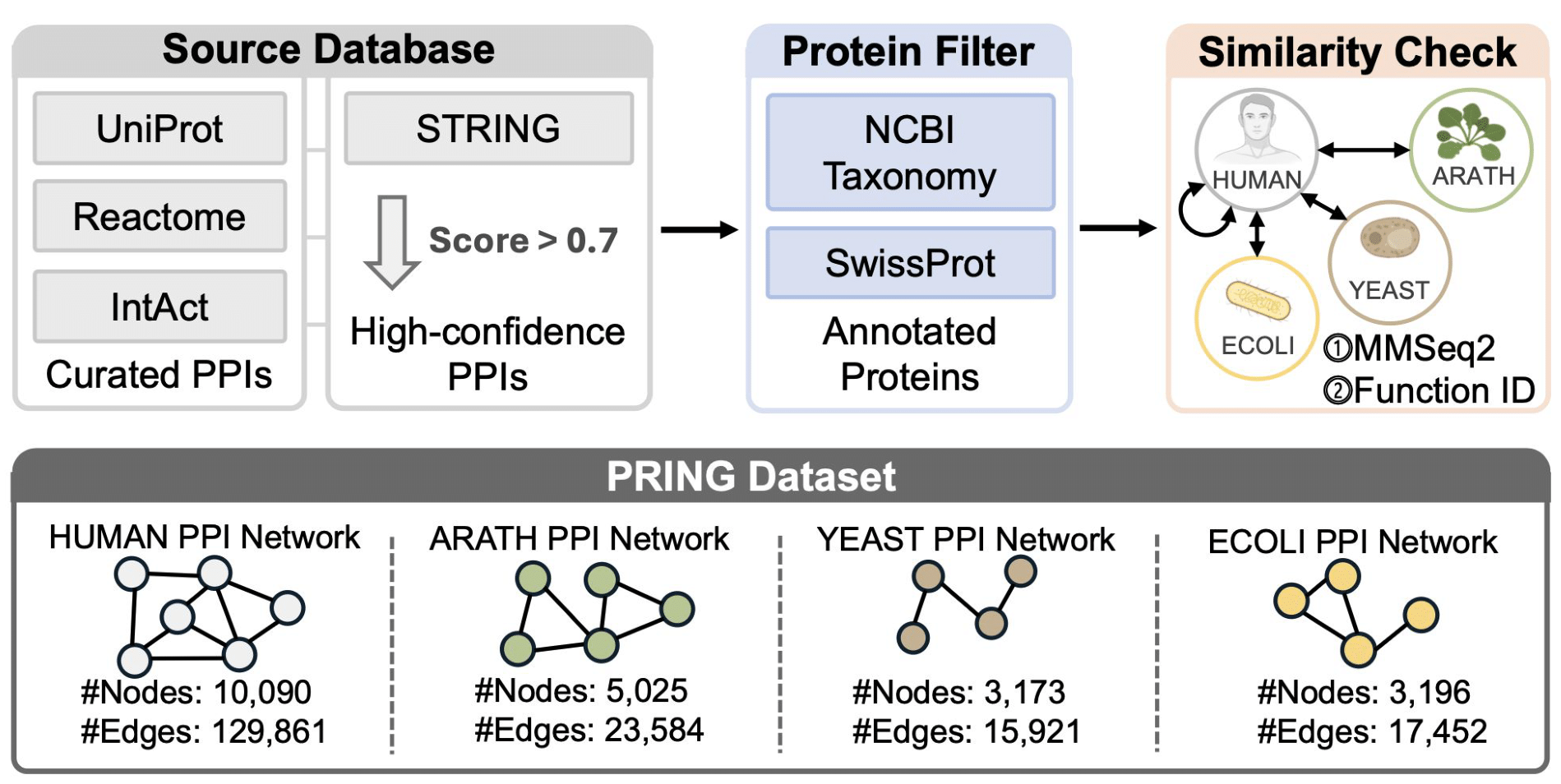

PRING (Protein–Protein Interaction prediction from Graphs), which was published at last NeurIPS, addresses this by providing a benchmark to evaluate PPI predictors at the graph level, not just pairwise classification. It comes with a curated multi-species dataset designed to reduce common pitfalls like leakage, and asks whether your model can recover both:

- Topology: does the predicted graph “look like” real biology?

- Function: does the graph support biological discovery tasks?

At a glance, PRING contains ~21k proteins and ~200k PPIs across 4 diverse organisms, assembled from major interaction resources (STRING, UniProt, Reactome, IntAct). To control redundancy, PRING applies sequence-similarity filtering (reported at 40%) and uses a leakage-aware split that avoids overlapping proteins between train/test. The full dataset is available on HuggingFace 🎉.

PRING dataset overview (PRING paper).

PRING dataset overview (PRING paper).

Topology-oriented tasks: does the predicted network look like a true network?

Pairwise accuracy can tell you whether you got many edges right, but not whether those edges assemble into a plausible network. PRING tests this with tasks such as:

- Human interactome reconstruction (intra-species): train on a subset of the human PPI network, predict edges for held-out proteins, and check whether the resulting graph resembles a real interactome. If almost every protein connects to everything, it’s not credible, even if many edges are correct.

- Cross-species generalization: train on one species and reconstruct PPIs in another (e.g., human → yeast), probing whether the model learned transferable interaction principles rather than memorizing species-specific pairs.

Predicted networks are compared to ground truth using intuitive graph-level checks such as graph similarity (do we recover the same edges) and degree distribution (do we get realistic hubs vs a “hairball”), among others.

Function-oriented tasks: does the predicted network support known biology?

Even if a predicted network looks plausible, the key question is whether it supports downstream reasoning. PRING includes tasks like:

- GO module analysis: do network communities correspond to coherent biological functions? If a community contains proteins involved in the same process, it’s a sign the structure is meaningful.

- Essential protein justification: do known essential proteins show up as central in the reconstructed network? In real interactomes, core processes often sit at the center of dense neighborhoods.

PRING quantifies these with module-level alignment and centrality-based separability.

Benchmarking diverse PPI methods

PRING evaluates sequence-similarity baselines, “classic” deep sequence models (including physicochemical features), PLM-based approaches, and structure-based methods. The headline takeaway isn’t “one model wins forever.” It’s that strong pairwise performance doesn’t guarantee strong network behavior, and even the best models still struggle to fully recover both topology and biological function.

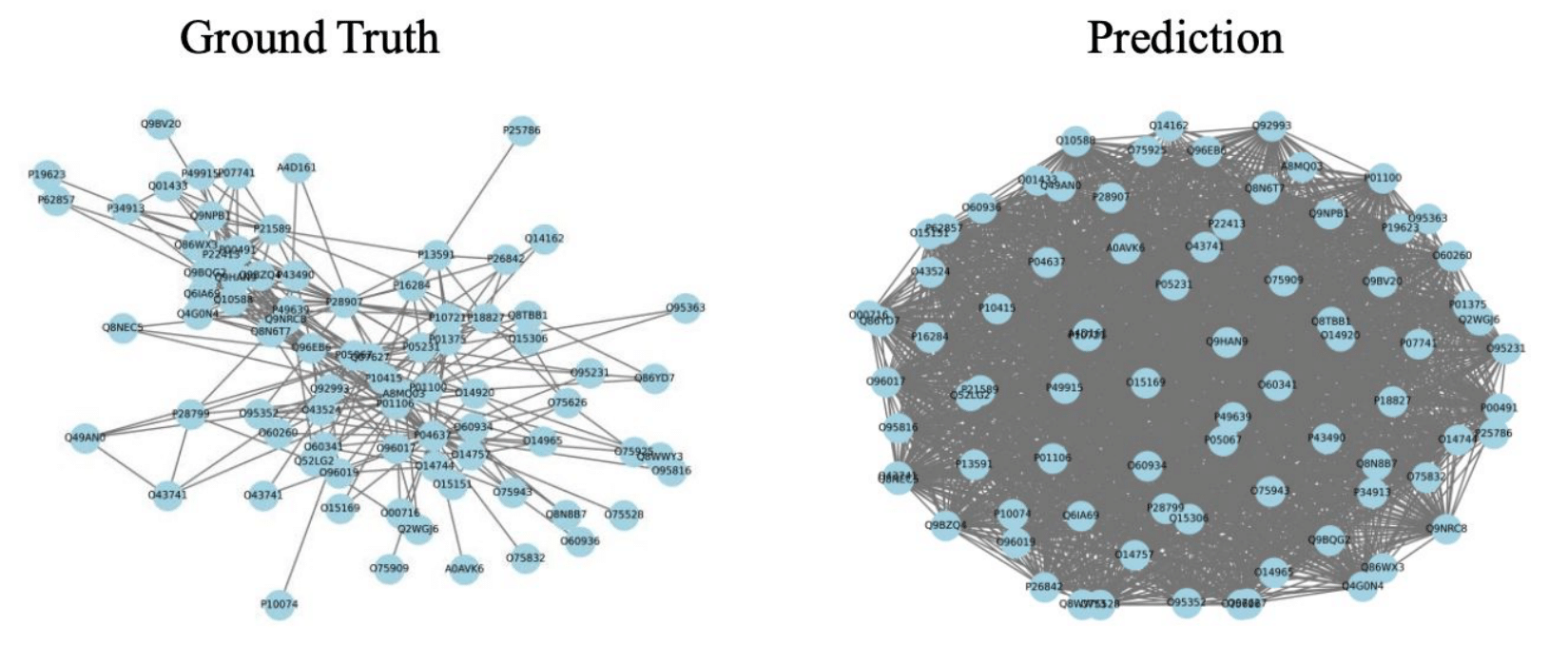

PRING makes this visible by exposing failure modes that AUC can hide: networks that are too dense or too fragmented, miss key hubs, or fail to preserve coherent functional modules.

True vs Predicted PPI subgraph using Chai-1 structural model (PRING paper).

True vs Predicted PPI subgraph using Chai-1 structural model (PRING paper).

Bridging the gap: from pairs to systems biology

PRING pushes PPI modeling toward what real applications need:

- Target safety & mechanism: does perturbing a target destabilize complexes, rewire modules, or hit central hubs?

- Better model development: graph-level evaluation surfaces failure modes pairwise metrics can miss.

- Cross-species transfer: stress-test generalization in a way that matters for using model organisms.

In summary, PRING lets the community compare models on what matters in practice: whether predicted PPIs assemble into biologically plausible, useful networks. Make sure to check out the PRING paper, the dataset on Hugging Face as well as the code!

Ready to try it?

Use a PRING network explorer to visualize true vs predicted PPI graphs: